ON BELONGING WITH SUWON LEE

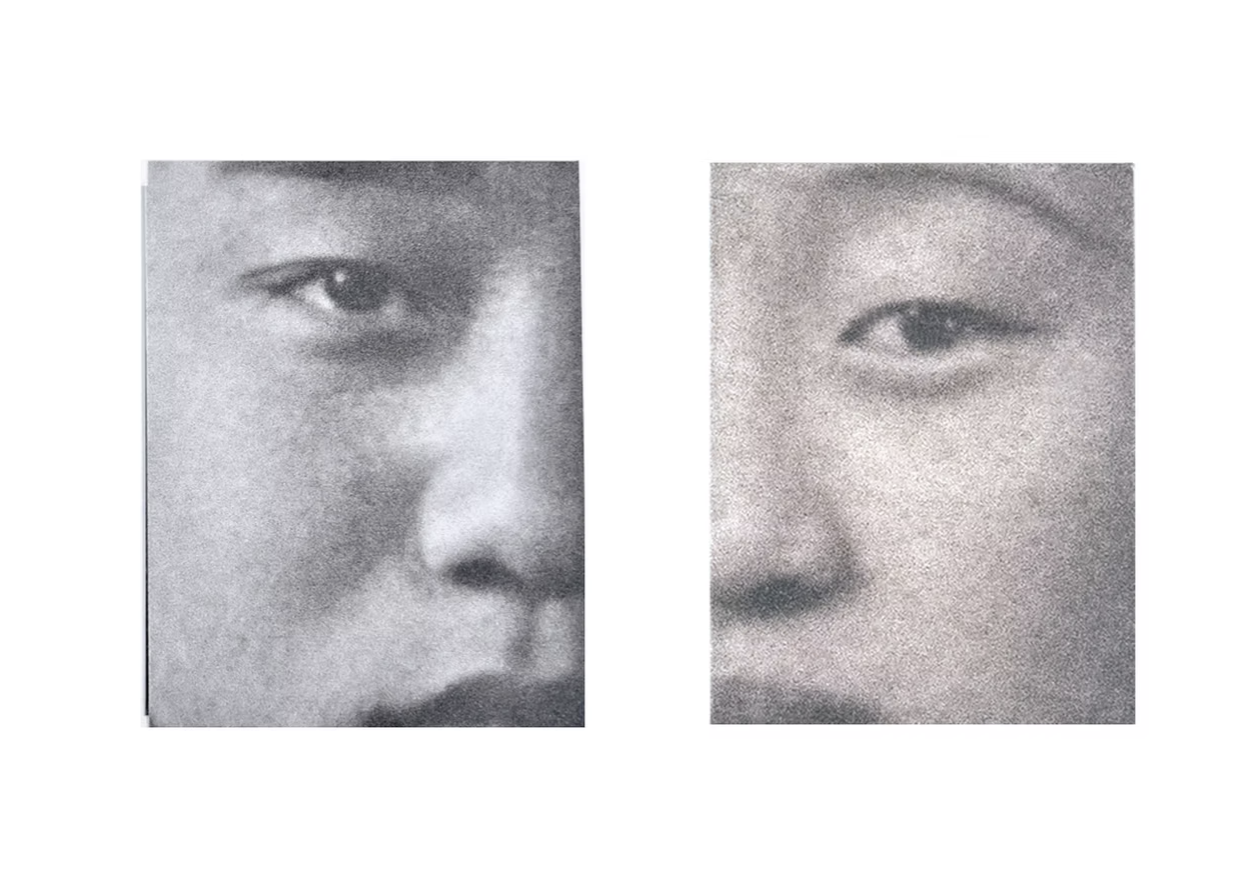

Suwon Lee, Mr. & Mrs., 2021, Artist’s book.

Currently based in Spain, Suwon Lee is a Korean Venezuelan artist belonging to the recent Venezuelan diaspora, whose work explores space, time, place, and belonging.

In light of this month’s theme of the pursuit of imperfection, we asked Lee about her photobook Mr. & Mrs., a collection of photographs honoring the lives of her Korean grandparents, and how she navigates her multi-layered identity.

Where (if ever) do you notice yourself trying to perfect belonging instead of letting it be messy?

I learned early on that trying to fit in was useless. Changing who I was felt dishonest, like a small betrayal. When I was eight, I tried to rename myself “Susan” because people made fun of my real name. It didn’t last long; I never felt like a Susan (lol). Even now, people are flabbergasted to see my Asian face speaking perfect Venezuelan Spanish, as if that combination shouldn’t exist. I’ve always felt like a freak, and for a long time, that feeling was deeply uncomfortable. The difference is that, from my late thirties on, I learned to trust that discomfort instead of trying to correct it. I finally felt at ease in my own skin. Refusing to betray who I am has become my only reliable definition of belonging.

“I made a quiet decision there: if I don’t belong to a society, I will belong to the land.

The land holds me without asking who I am. This is true grounding.”

When you think about “imperfect belonging,” where does that idea land in your own life right now?

Since leaving Venezuela in 2016, I haven’t felt fully integrated in any of the places I’ve lived: Panama, Korea, or Spain. I’ve become a foreigner, a stranger, something I already was in Venezuela, but now in the condition of an immigrant. After five years in Madrid, I grew tired of city life and longed for a deeper connection to nature. That desire led me to the edge of the Valencian Huerta, a peaceful agricultural landscape shaped by irrigation, labor, and memory. I made a quiet decision there: if I don’t belong to a society, I will belong to the land. The land holds me without asking who I am. This is true grounding.

Could you share how Mr. & Mrs. came to be, and what guided your decision to have your grandparents’ eyes don the cover?

Mr. & Mrs. began in 2018, when I moved back to Korea after leaving Venezuela and a brief period in Panama. Returning to my father’s home in Seoul marked a moment of rupture and reorientation. Shortly after arriving, I discovered stacks of his family photo albums, forgotten in a corner of the room. Moving through them decade by decade felt like watching my family’s life unfold like a film, revealing relatives I had never known and moments I had never seen. The project emerged from listening to that archive and to my father as he named each person and shared his own memories, rather than trying to complete or correct the past. Choosing my grandparents’ eyes for the cover felt instinctive. Their gaze resists time, creating an intimate exchange between past and present, while quietly normalizing Asian presence without exoticizing it.

With an archive of more than 1,300 photographs, how did you decide what to keep, what to omit, and what story these images would ultimately tell?

Since my grandparents were the gatekeepers of these memories and the central protagonists of the archive, their images were the most abundant. I began by selecting every photograph in which they appeared, eventually narrowing the material down to ninety images of each. Many of these were group photographs, so I cropped them to isolate their faces, treating them almost like headshots. This allowed me to maintain a frontal gaze and to construct a visual timeline for each of them, almost like a flipbook, where time unfolds through subtle shifts in expression, age, attire, and the changing photographic formats of each era.

In a past interview, you said, “Remembering—even when painful—is vital to understanding who we are and ensuring that those memories do not fade with time.” While shaping Mr. & Mrs., what did you learn about yourself or your lineage that you hadn’t expected?

While working on Mr. & Mrs., the photographs opened my grandparents’ world to me. They revealed faces and stages of their lives I had never seen before, allowing me to encounter them beyond the fixed role of grandparents. Through small gestures, I began to sense ways of facing adversity that were never fully spoken about within the family. I also realized how intentionally they documented their lives, preserving small proofs of their existence. My grandmother, in particular, collected portraits from every stage of her life, and my grandparents even preserved the only surviving images of the Korean restaurant my parents ran in Caracas in the 1980s. Without them, that chapter of our family history would have no visual memory. Making this book became a way of sitting with my family’s history and its traumas. It is not a happy story, but seeing my grandparents as whole beings, rather than only as grandparents, softened my gaze. It allowed me to be less judgmental, and to move toward acceptance, forgiveness, and gratitude.

You worked with Horacio Fernández to shape the written voice that accompanies these images. What did it mean to let someone outside your family and outside your cultural history interpret your archive? What did that collaboration open up for you?

I first met him many years ago when he came to Caracas to give a talk. We reconnected in Madrid in 2020, during a master’s program where he taught the history of the photobook. It was there, while developing a dummy as an assignment for his class, that Mr. & Mrs. first took shape. The collaboration emerged from a long and generous conversation. I shared the project with Horacio at an early stage, and he immediately connected with its emotional dimension. His text is based on the stories I told him about my grandparents and my family, stories passed down to me by my father. Rather than explaining the images, his words accompany them, opening them up and giving them air. Working with Horacio was a true gift. It taught me the power of synthesis, rhythm, and restraint: how words, like images, can carry weight through economy, precision, and poetic force.

Did your Venezuelan upbringing influence the way you approached your Korean family archive? Were there moments when the two cultural lenses collided, blurred, or clarified each other while you were editing the book?

Growing up in Venezuela, far from most of my relatives, was deeply lonely, and I longed for a sense of connection to them. That distance turned family into a kind of mystery, filled with unanswered questions. When I eventually encountered the archive, I cherished the discovery intensely. I don’t think my cousins relate to it in the same way, perhaps because they grew up without that sense of longing, surrounded by family rather than separated from it. There is also my sensitivity to the photographic image, which shaped how I approached the archive. I think it was the convergence of those two factors, the emotional distance and my relationship to photography, that proved crucial in shaping the project.

“I work through fragments, repetition, and gaps because that is how my own sense of belonging was formed.”

Among other cities, you’ve lived across Venezuela and Korea—two places with very different cultures, languages, rhythms, and expectations. How did moving between those worlds shape the way you understand yourself today?

Venezuela and Korea are not just different; they often feel diametrically opposed. Venezuela, as a Caribbean and deeply diverse culture, is shaped by warmth, spontaneity, and generosity, with a strong sense of joie de vivre. Korea, in my experience, is more culturally homogeneous and more emotionally restrained, with relationships structured by hierarchy, formality, and social codes that leave less room for difference. What is embraced with curiosity in Venezuela can feel more cautiously received in Korea. At the same time, Korea carries a deep sense of loyalty and devotion, particularly within families. These are, of course, personal impressions rather than fixed truths, but moving between these worlds has meant constantly negotiating how much of myself I can offer and how much is received in return.

That adaptability sharpened my awareness, but it also produced a lasting sense of in-betweenness, of never fully arriving in a single place or definition of self. Living across these worlds made me attentive to what doesn’t translate: gesture, silence, emotional codes, and inherited behaviors. That sensitivity now shapes my artistic practice. I work through fragments, repetition, and gaps because that is how my own sense of belonging was formed. Rather than resolving contradictions, I let them coexist. In that space between cultures, I’ve come to understand myself not as unfinished, but as layered, and it is from that layered position that my work speaks.

It has now been a few years since Mr. & Mrs. was published, and with Family Atlas, you returned to the archive from a different angle, continuing your family’s history from Korea to Venezuela. What questions about memory or identity come up for you now than when you first began this work?

When I first began Mr. & Mrs., my focus was on recovery and proximity, on finding a way to approach a family history that felt distant and incomplete. Memory, at that moment, was something fragile, something I felt an urgency to preserve before it disappeared. Identity was closely tied to inheritance, to what had been passed down and what had been lost. Returning to the archive through Family Atlas shifted those questions. Instead of asking how to remember, I became more interested in how memory is preserved and organized outside of chronology or formal systems, in ways that are informal, intuitive, and sometimes seemingly random. After completing these two series, I feel that I’ve established a kind of foundation. More than generating new questions, the work helped me place a missing piece of the puzzle. With that piece in place, I feel freer and more grounded, able to layer other works on top of it and to relate my previous projects to one another. It feels like building a topography of memory, where new layers can continue to accumulate without destabilizing what lies beneath.

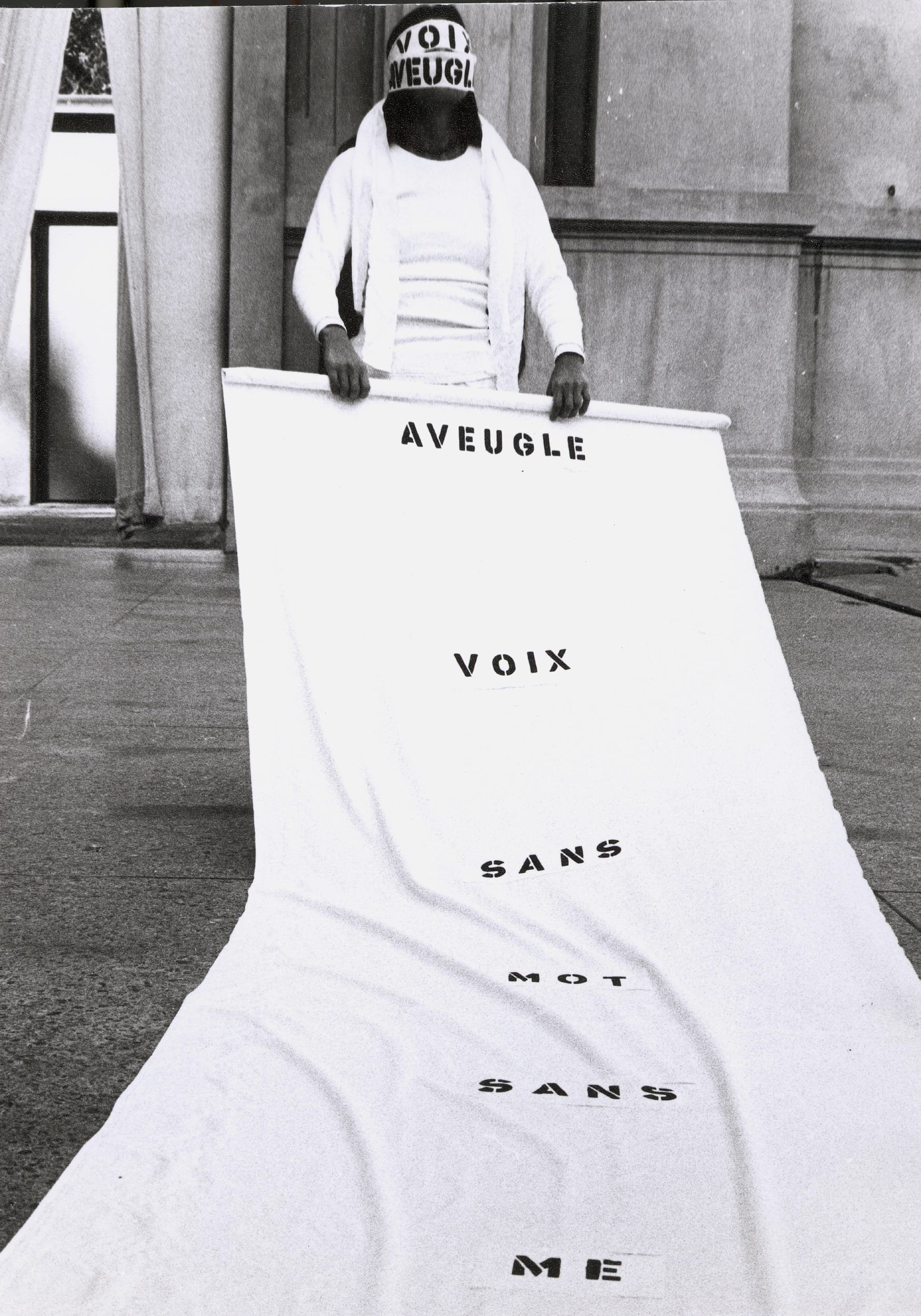

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Aveugle Voix, 1975, performance.

To close, we ask each contributor to share one recommendation from any global diasporic community—a book, artist, archive, musician, exhibition, or even one photograph—that has stayed with you. What’s one you’d love our readers to know?

I would choose Aveugle Voix, a photograph from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s performance of the same name. When I first saw it, I felt an immediate sense of recognition. It captured something I had experienced but couldn’t fully articulate: the feeling of being both voiceless and isolated after being uprooted from one’s home country. Exile can interrupt language, perception, and a sense of agency all at once. Many readers may already be familiar with this image, but it remains deeply poignant and brutally powerful in how it makes the migrant experience visible.

CATCH SUWON LEE’S UPCOMING SOLO EXHIBITION IN BARCELONA, featuring her work La montaña sagrada, along with a new piece composed of two interwoven photographs of her grandparents and a collage series inspired by a performance she presented in 2025 in New York.

To Learn more about Suwon LEe’s Work, visit her website & follow her on Instagram.

FOR MORE RECS LIKE THIS ONE, CHECK OUT THE REST OF VOL. 001: